From economist Mark J. Perry:

Inspired by Equal Pay Day, I introduced “Equal Occupational Fatality Day” in 2010 to bring public attention to the huge gender disparity in work-related deaths every year in the United States. “Equal Occupational Fatality Day” tells us how many years into the future women will be able to continue to work before they will experience the same number of occupational fatalities that occurred for men in the previous year.

The Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) released data this week on workplace fatalities for 2016, and a new “Equal Occupational Fatality Day” can now be calculated. As in previous years, the graphic above shows the significant gender disparity in workplace fatalities in 2016: 4,803 men died on the job (92.5% of the total) compared to only 387 women (7.5% of the total). The “gender occupational fatality gap” in 2016 was again considerable — more than 12 men died on the job last year for every woman who died while working.

Based on the BLS data for 2016, the next “Equal Occupational Fatality Day” will occur more than 10 years from now – on May 30, 2028. That date symbolizes how far into the future women will be able to continue working before they experience the same loss of life that men experienced in 2016 from work-related deaths. Because women tend to work in safer occupations than men on average, they have the advantage of being able to work for more than a decade longer than men before they experience the same number of male occupational fatalities in a single year.

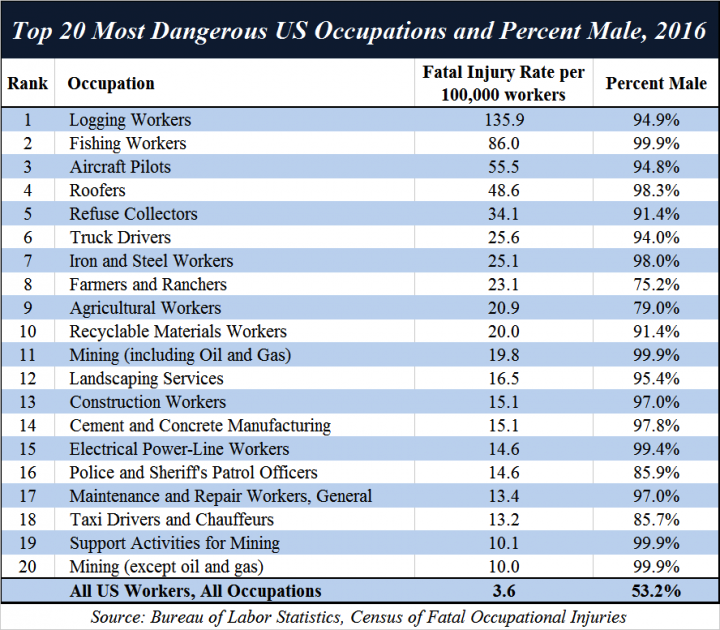

Economic theory tells us that the “gender occupational fatality gap” explains part of the “gender earnings gap” because a disproportionate number of men work in higher-risk, but higher-paid occupations like coal mining (almost 100% male), commercial fishing (99.9% male), police officers (85.9% male), logging (94.9% male), truck drivers (94.0%), roofers (98.3% male), and construction (97.3% male); see BLS data here. The table above shows that for the 20 most dangerous US occupations based on fatality rates per 100,000 workers by industry and occupation in 2016 men represented more than 90% of the workers in 14 of those 20 occupations, and more than 85% of the workers in 18 of the 20 occupations.

On the other hand, women far outnumber men in relatively low-risk industries, often with lower pay to partially compensate for the safer, more comfortable indoor office environments in occupations like office and administrative support (72.1% female), education, training, and library occupations (73.1% female), and healthcare (75.6% female). The higher concentrations of men in riskier occupations with greater occurrences of workplace injuries and fatalities suggest that more men than women are willing to expose themselves to work-related injury or death in exchange for higher wages. In contrast, women, more than men, prefer lower risk occupations with greater workplace safety, and are frequently willing to accept lower wages for the reduced probability of work-related injury or death. The reality is that men and women demonstrate clear gender differences when they voluntarily select the careers, occupations, and industries that suit them best, and those voluntary choices contribute to differences in pay that have nothing to do with gender discrimination.